What are the most common obstacles to successful employment encountered by people with ASD

Many people associate work with stress, expectations around productivity, and social situations which can be overwhelming or frustrating. For individuals with autism spectrum disorder, these difficulties are often magnified. Studies show that people with autism have markedly different vocational needs than individuals with other developmental disabilities (E. Billstedt C. G., 2005).

Communication and Social impairment

That autistic people are disadvantaged is not surprising, given how we have built a world heavily dependent on tight social coordination with others. Work can be an inescapably social environment, with its own unwritten rules and customs which can be difficult to navigate for anyone, especially those dealing with ASD. Access to any employment opportunity requires candidates to navigate the social encounter of the interview, while even getting to the stage of an interview in the first place requires the ability to build social capital and network with others. For people who have life-long difficulties in social interaction, the social process of finding employment remains a considerable obstacle. A lack of eye contact, or a silence that lasts too long can have very negative consequences for rapport. Yet autistic people may give off these signals unintentionally, which is why employers need to look past small-scale social cues to take a broader perspective on what is meaningful interaction.

Due to the variety of characteristics across the diagnostic criteria for autism, and the spectrum of need and ability make the provision of successful employment a great challenge indeed (J.H. Keel, 1997). According to Simpson, the countless permutations and combinations of social interactions, language, learning, sensory, and behavior deficits and excesses found in these individuals, in combination with their wide range of abilities, developmental levels, isolated skills, and unique personalities make autism an especially baffling disability (Simpson, 2001)

According to literature, interactional difficulties associated with ASD have the biggest vocational impact (D. Hagner and B.F. Cooney, 2005). More specifically, communication and social difficulties with supervisors and co-workers considerably hinder job performance (Magill-Evans, 2001) . Communication obstacles include difficulty understanding directions; inability to “read between the lines”, read facial expressions, and tone of voice; asking too many questions; and communicating in an inappropriate manner (Chalmers, 2004). Social difficulties are deficits intrinsic to successful interactions and may include inappropriate hygiene and grooming skills, difficulty following social rules, inability to understand affect, working alone, and acting inappropriately with individuals of the opposite sex (Magill-Evans, 2001). These difficulties can often affect also mastering the job application and the interview process.

Cognitive Functioning

Additionally, Impairments in executive functioning are well documented in individuals with ASD and can affect job performance. Many exhibit difficulties in task execution due to problems with attention, motor planning, response shifting, and working memory (E. Müller, 2003) . Adapting to new job routines and managing changes in the work setting often pose a challenge (J.H. Keel, 1997). People with ASD can have difficulties with both problem-solving and organization, despite having average or above-average intelligence (Barnhill, 2007).

According to Howlin (2000), many may experience difficulty in fulfilling employment roles as they get older due to a deterioration in skills that may occur in early adulthood for those who have low IQs or develop epilepsy.

Behavioural Difficulties

Behavioral difficulties such as tantrums, aggression, self-injury, property destruction, ritualistic behaviors, or pica can create an employment barrier. Interfering behaviors create a complicated issue as many are misinterpreted, have multiple functions, and require multi-faceted behavior management strategies (Carr, 1995). Such behaviors are not well tolerated in the workplace and may prevent employment all together and lead to segregation (H, 1990).

Stress and Anxiety

As a result, individuals with ASD report high levels of stress and anxiety which may interfere with performance. Hurlbutt and Chalmers (Chalmers, 2004) interviewed six adults with ASD who reported high levels of anxiety due constantly trying to fit in socially with the neurotypical world. Additionally, Burt et al. (D.B. Burt, 1991) found that individuals with autism had increased anxiety due to sensitivity to workplace noise and other sensory stimuli. In another study, parents reported anxiety as a major obstacle for postsecondary success due to their child’s fear of the unknown and navigating social interactions. (Sarigiani, 2009).

Sensory Sensitivity

Sensory stimulation on the job site in the form of phones ringing, conversations between co-workers, and other distractions can also prove overwhelming. These challenges necessitate the development of healthy coping strategies and plans for difficult scenarios. They also require communication with co-workers and bosses to make the workplace a friendlier environment.

Comorbidity with a variety of psychiatric symptoms

Finally, the comorbidity with a variety of psychiatric symptoms including depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder in individuals with ASD has been widely reported (M. Ghaziuddin, 2002), with epilepsy occurring in approximately one-third of the population (Yang, 2005). It is a fact that such mental and physical health problems may significantly interfere with the capacity for positive employment outcomes. Schaller and Yang (Yang, 2005) used the 2001 Rehabilitation Services Administration database to describe the demographic characteristics related to employment by the 815 individuals with ASD who achieved competitive and supported employment outcomes. Absence of a secondary disability was significantly related to successful competitive employment

Social imagination

It is true that some people with autism have active imaginations, are very creative, and may be successful musicians, artists and writers. However, people with autism generally lack social imagination, which means they may find it difficult to understand and interpret other people’s feelings, thoughts and actions. They can also have difficulties to pick up cues and predict what will happen next and to understand the concept of danger. This affects the way they prepare for change and plan for the future, and it is why they find it hard to cope with change and unfamiliar situations. (Autism Europe, 2014)

Discrimination in relation to employment

Unfortunately, this can occur at many different stages of the employment process and can take a multitude of forms, with the most obvious form being during the recruitment process, which can be very difficult for a job applicant to prove. Moreover, while a person with autism may face discrimination at work, they may not recognise when they are being discriminated against, or lack understanding of their rights and how to exercise them. In fact, a study of legal cases in the United States in which people with disabilities who were employed alleged that they had experienced discrimination from their employers found that people with autism were less likely to make claims about discrimination than people with other disabilities. (Autism Europe, 2014)

Lack of autism training

At the environmental level, some have posited that the real barriers to employment for this group lie not in the socially atypical mannerisms of ASD but instead in society's labeling of the idiosyncrasies associated with ASD as “deficits” instead of positive attributes in the workplace (T. Lorenz, 2016). Much of the current research indicates significant gaps in understanding the daily challenges that prevent those with ASD from maintaining meaningful employment.

Misunderstandings

As a result, there is a huge gap in communication between neurotypical and neurodiverse individuals. Brett Heasman, (Heasman B, 2018) who specialises in public understanding of autism, states that employers often think they’re communicating well, but they use ‘neurotypical’ standards of interacting, writes.

Heasman, explains the theory of the “double empathy problem”. This starts with the fact that autism is a ‘hidden’ disability, with no external physical signs and most non-autistic people are not aware of the complex ways in which autistic people experience the world and are not adequately prepared for interacting or working with autistic people.

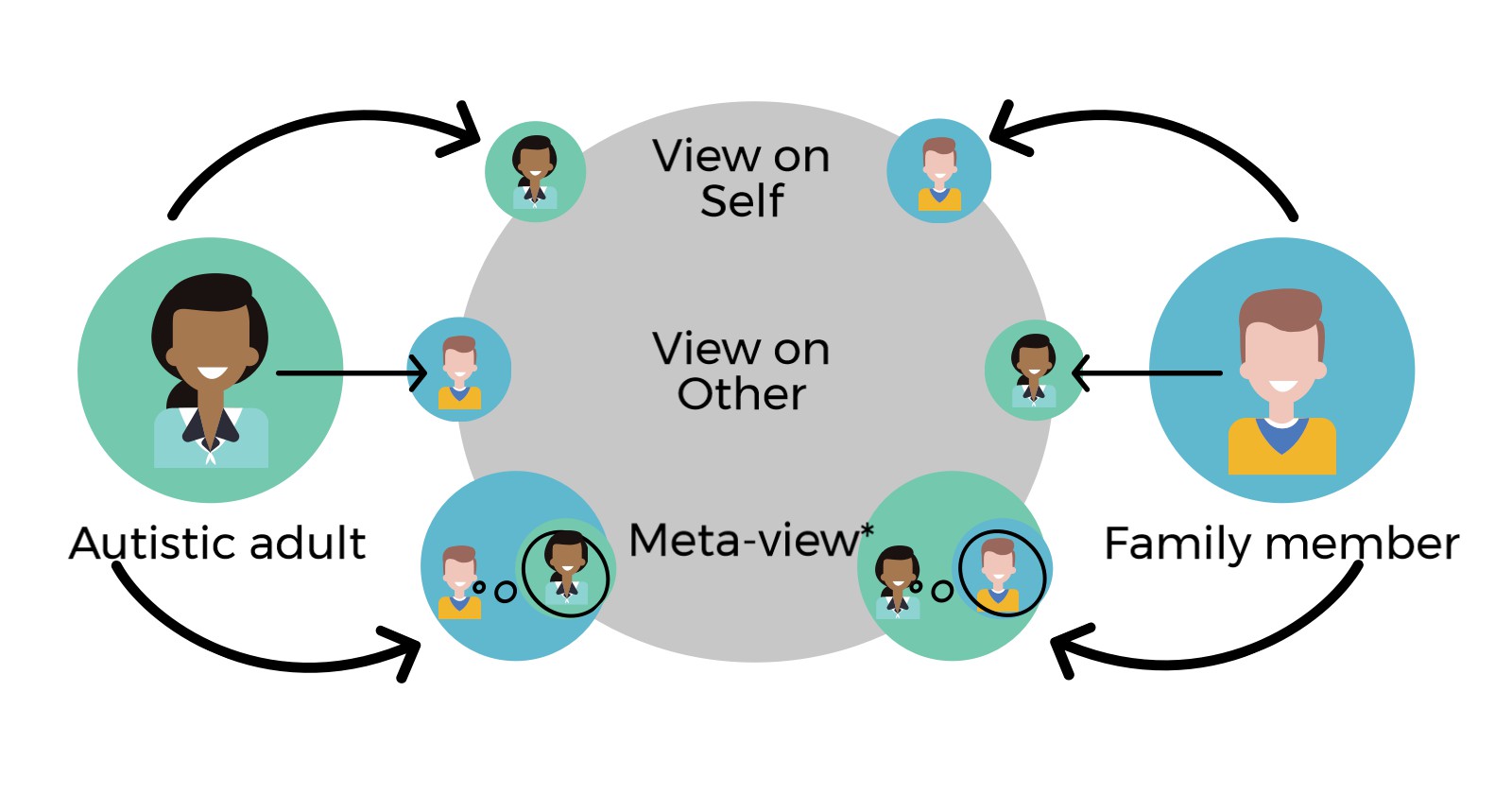

Building professional relationships is another critical issue. A recent study (you can find the study here: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1362361317708287) ;(Heasman and Gillespie, 2017), has shed new light on why this may be the case. They examined family relationships between autistic adults and their family members and found that many misunderstandings did not always originate from the autistic adult. Family members were often incorrectly taking the perspective of autistic relations, seeing them as more ‘egocentrically anchored’ in their own perspective than they actually were. This misunderstanding raises an important question regarding the assumptions used by non-autistic people to evaluate autistic people. It is evidence of the ‘double empathy problem’, a persisting gap in mutual understanding because both sides of a given autistic/non-autistic relationship have different normative expectations and assumptions about what the ‘other’ thinks.

Let’s look into some real examples from a Heasman’s case study:

An autistic person reported feeling uncomfortable with the constant change to his work schedule, and did not like having to attend meetings particularly because it left him feeling criticised which would inevitably affect his other activities for the day. From the employer’s perspective, they were very keen to show that they had been adapting to his particular way of working within what they perceived to be reasonable adjustments. It turns out that during meetings the autistic employee would often misunderstand what had been said. In response, the employer stressed that they had no problem with the meeting being stopped if the autistic employee wanted to ask a question or clarify a point of discussion. This can be a problematic assumption though, because the autistic employee may not realise a misunderstanding has taken place until much later, when it had manifested into a problem, and even if he did recognise the misunderstanding instantly, it should not be assumed that he would be able to “speak up” instantly. Speaking up is a very complex social skill. It requires for the person assess the dialogue, look for moments of verbal interjection, and give a non-verbal signal to join in the discussion just prior to speaking.

Another challenge was the employer was focusing a lot on ‘constructive criticism’ in order to improve the way in which the team worked as a whole. It was suggested that running over the positive things which the autistic employee had done would be a good idea. From the employer’s perspective, this had not seemed particularly necessary because many of the positive aspects were deemed obvious. However, when the autistic employee was asked, it was very clear that he had no idea what it was that he did well, and because of his low self-esteem, would often downplay compliments.

Therefore, the employer should have been giving much more positive feedback, even on tasks that seemed obvious, because it cannot be assumed that the employee shared the same level of certainty about what was good or bad practice.

These two examples show how the employer believed good communication was already in place, when in fact communication was based on ‘neurotypical’ standards of interacting. There is no doubt that the employer was keen to do the best for managing the professional relationship and had already made many adjustments, but these examples show how deep-rooted our social reading of others is ingrained, and how much opportunity remains to improve public and employer understanding of autism through listening to what autistic people have to say.

Figure 1. Psychological structure of relationships (Heasman and Gillespie, 2017)

Notes: * Meta-view = how one person thinks they are seen by the other person. Misunderstandings can easily persist if one’s meta-view aligns closely with one’s view on the other. Source: Heasman and Gillespie, 2017.

To conclude, a small body of work has also begun to examine barriers to employment for those on the autism spectrum, and ways to overcome them. The findings highlight the value of work experience, internships and supported employment schemes. For example, a study of autistic adults (aged 21–25 years) in the United States revealed employment rates that were over twice as high for those who worked for pay during high school (90%) versus those who did not (40%). Similarly, a US internship programme that arranges work placements for young autistic adults that are embedded within a community business (e.g. banks, hospitals or government departments), has shown very positive findings. A comparative study found that 87.5% of participants in the group who participated in the scheme achieved subsequent employment, compared to 6.25% in the group who did not take part. (Pellicano, 2017)

Discrimination

Following the indications of the Report on good practices in employment for people with autism from across Europe, we are going to identify the barriers to employment that people with autism face are not only caused by their disability. They also face much stigma and discrimination when trying to get or maintain a job. Despite that, adults with autism often really want to work and can be exceptionally capable of doing particular jobs. They simply need assistance to overcome the barriers and difficulties they face.

Download