There is no doubt that autism is a biological disorder that is defined through behavior. There have been several attempts to make a connection between presumed biological dysfunction and atypical behavior and thus explain the essence of autistic disorder. The three most influential hypotheses that explain a wide range of clinical manifestations in autism are: the theory of mind hypothesis, the executive dysfunction hypothesis, and the weak central coherence hypothesis.

Theory of mind hypothesis

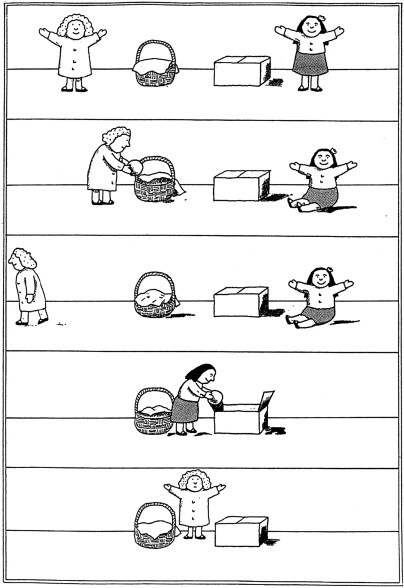

The theory of mind is the ability to attribute mental states (thoughts, desires, beliefs, intentions, etc.) to other people. Only if we understand other people's mental states can we correctly interpret what someone said, understand the meaning of his behavior and predict what that person will do next. One of the classic tests for examining the theory of mind is the task of false belief (Baron-Cohen et al., 1985). The picture shows two girls, Sally and Anne. Sally puts the ball in the basket and exits. Anne moves the ball from the basket to the box. The question is where Sally will look for the ball when she returns. To give the correct answer that Sally will be looking for the ball in the basket we need to understand that she could not see that the ball had been moved and hence believe that it is still in its original place. Baron-Cohen et al. (1985) find that four-year-old children of typical development successfully solve the problem of false belief, while children with autism fail to solve it. After this, initial research, the theory of mind was tested in different populations, and various tests were created to assess different aspects of this ability.

Sally-Anne false belief test

In people of typical development, the ability of the theory of mind is acquired spontaneously, while children with autism have great difficulties in understanding numerous mental states. Many atypical behaviors of people with autism, especially in the domain of social communication, can be explained by the deficit of the theory of mind. Howlin et al. (2002) cite the following consequences of the deficit theory of mind:

Insensitivity to other people’s feelings (for example, an employee with autism comments on the appearance of colleagues without realizing that it may offend them)

Inability to take into account what other people know (for example, a person with autism who has noticed a malfunction on a device does not realize that the employer may not be aware of this fact)

Inability to negotiate friendships by reading and responding to intentions (for example, an employee with autism does not respond to a greeting)

Inability to read listener’s level of interest in one’s speech (for example, it happens that a person with autism is fascinated by certain topics that he knows a lot about and can talk about them for a long time, without realizing that other people may not be interested in that topic)

Inability to detect a speaker’s intended meaning (for example, to the ironically remark of a work instructor that he should stop or break a machine a person with autism could really do it)

Inability to anticipate what other’s might think of one’s action (for example, an employee with autism gets too close to colleagues during a conversation, touches them or takes their belongings without evaluating how others might react)

Inability to understand misunderstandings (for example, a person with autism does not understand that other people's behavior is sometimes motivated by some confusion and misunderstanding)

Inability to deceive or understand deception (for example, an employee with autism does not understand that someone is exploiting or cheating him)

Inability to understand the reson behind people’s actions (for example, an individual with autism does not understand why two colleagues who have quarreled do not want to work together)

Inability to understand unwritten rules or conventions (for example, a person with autism does not know when and how to wish a happy birthday, express condolences, wish luck, etc).

Work instructors, employers and colleagues who gain basic information about the theory of the mind of people with autism will be inclined to attribute atypical forms of behavior of workers with autism to their misunderstanding of other people's mental states, and not to bad upbringing or malice.

Executive dysfunction hypothesis

Although there is no single definition of executive functions, this term is commonly used to denote a broad range of high-level cognitive functions, such as planning, cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, working memory, and so on. Numerous studies show that children and adults with autism have less developed executive functions compared to neurotypical subjects of similar age and intellectual abilities. Involvement in the world of adults implies the ability to control emotional reactions, careful planning and execution of tasks, directing attention to the context in which a certain activity is carried out, etc. (Kim et al., 2021).

The lack of executive functions in the work environment can be manifested through:

1. difficulties for employee with autism to plan their activities and the time needed to perform them, to follow the set plan and to correct mistakes

2. resistance to change, difficulties in switching from one task to another or adopting new rules of work imposed by current circumstances, although they may be quite contrary to the rules in force until then

3. problems in remembering the request, the exact order of activities and the location of a significant item

4. inability to ignore information that is not relevant to the performance of work activities or to interrupt their own activity that does not lead to the expected results.

5. the tendency of employees with autism to perform repetitive activities in the same way

6. difficulties in disengaging attention, "detaching" attention from the object of interest to events in the work environment in which other colleagues are interested

7. inflexibility in the organization of work and difficulties in accepting changes in the duration of working hours, the dynamics of the use of vacation, etc.

Therefore, the deficit of executive functions can explain both the social and non-social characteristics of autism. Narrow, limited interests, repetitive activities, perseverations in speech and behavior can be linked to a lack of cognitive flexibility. At the same time, appropriate social behavior is based on the ability to recall important information, inhibit inappropriate actions, flexibility, and the ability to monitor, update, and select socially appropriate responses (Leung et al., 2016).

Weak central coherence hypothesis

Neurotypical individuals tend to extract certain meanings from a range of stimuli, ignoring irrelevant aspects of the environment. Weak central coherence, which characterizes people with autism, indicates their preference for processing details, while neglecting the whole, which results in their inability to see the forest from the tree. People with poor central coherence have great difficulty integrating information they receive from different sources and cannot see the bigger picture. Sometimes it is difficult to determine clearly whether certain difficulties in performing work tasks can be related to a lack of central coherence or a deficit of executive functions. However, the following difficulties seem to indicate, at least in part, weak central coherence:

1. focusing on details while performing work tasks while ignoring other important factors such as time efficiency and fulfillment of global goals

2. the need for additional instructions on what the final product should look like

3. inability to determine priorities in performing work activity

4. multitasking difficulties and inability to cope with sudden requests or unexpected stimuli

5. impulsive behavior, based on a small amount of information.

None of these hypotheses can fully explain the complexity of the behavior of people with autism, nor the variability of the autism spectrum. Great research efforts are being made to establish complex links between theory of mind, executive functions and central coherence, not only in people with autism, but also in subjects with other disorders, as well as in neurotypical subjects.

Download